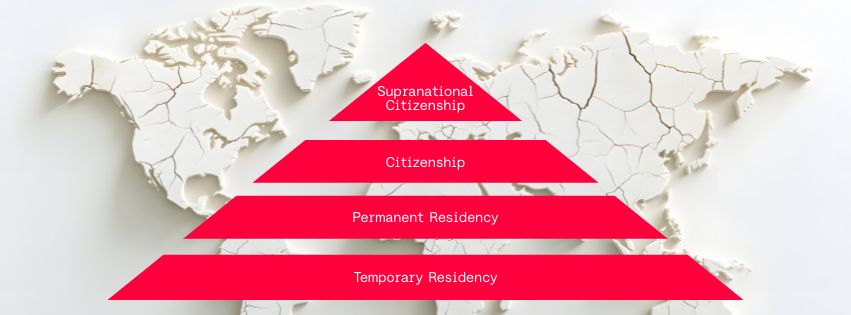

Governments do not simply sort people into citizens and foreigners; they manage a layered hierarchy of settlement rights that determines who may enter, who may stay, who may belong—and on what terms.

The invisible hierarchy of “who may stay”

Modern states operate less like gatekeepers of a simple border and more like managers of a stratified system of legal presence. Instead of one bright line between nationals and non‑nationals, they use several layers of status to calibrate rights, obligations, and long‑term belonging.

This layered structure is the missing context behind today’s battles over visas, golden passports, and migration crises. It explains why two people who both “live in the same country” can have radically different security, mobility, and futures.

Layer one: physical admission

At the base of the settlement pyramid is sheer admission—the right to cross the border and be physically present, even if only for a short and fragile period. This layer includes tourists, short‑term business visitors, and many temporary workers whose status is easy to grant and easy to revoke.

States treat this as the most flexible tier because it creates minimal political obligations: presence does not imply commitment or integration. Yet for millions, this precarious entry point is the only realistic contact they will ever have with a wealthy destination country.

Layer two: residence and renewal

Above admission sits residence, where people can lawfully live, work, study, and often bring family—usually conditioned on renewals, income thresholds, or ongoing compliance. Residence converts a fleeting stay into a life that can be planned, but it still depends on the state’s continuing consent.

Investment migration products—residence‑by‑investment or “golden visas”—operate primarily in this layer, selling relatively robust stay rights without immediately granting full political membership. This is where many high‑net‑worth individuals strategically position themselves to diversify risk across jurisdictions.

Layer three: secure permanent status

The third tier is permanent settlement, sometimes called permanent residence or an indefinite right to remain. Here, the individual’s ongoing presence is no longer tied to short renewal cycles, specific jobs, or discrete investment conditions.

This layer embodies a tacit promise that the state will not remove a person absent serious wrongdoing or exceptional circumstances. For migrants and investors alike, crossing this threshold transforms a portfolio “option” into a genuine second home base.

Layer four: full membership and citizenship

At the top is citizenship, which fuses legal security with political membership, typically adding rights to vote, access social protections, and transmit status to children. Citizenship is also the only layer that reliably travels: a passport projects settlement power outward by granting mobility and entry rights in other states.

Yet even here, gradations persist: some passports unlock entire regions through free‑movement zones, while others are little more than domestic identity documents. In effect, citizenship is both the summit of the national settlement pyramid and the starting point of a global hierarchy of mobility.

Why this pyramid matters for strategy

For investors, migrants, and policy‑makers, the settlement pyramid is a more precise strategic tool than talk of “passports versus visas.” It clarifies whether a given program sells admission, residence, permanence, or actual membership—and whether the promised path between those layers is real or illusory.

Understanding which layer is being bought, granted, or contested also reframes debates about fairness and sovereignty. The central question is not just “who gets in?” but “on which tier do they land, how easily can they climb, and who is structurally locked on the bottom rung?”

Source: Ahmad Abbas, “Climbing the 4-Layer Settlement Rights Pyramid”, IMI Daily